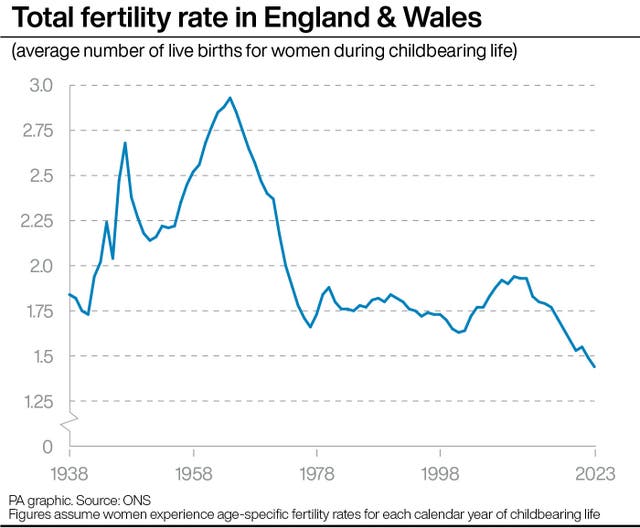

The total fertility rate across England and Wales dropped to a new record low last year, while the number of live births fell to the lowest in nearly five decades.

While fertility rates across the two nations have been in overall decline since 2010, the rate in 2023 fell to 1.44 children per woman, which the Office for National Statistics said is the lowest value since records began in 1938.

The rate was down from an average of 1.49 children per woman over their lifetime in 2022, and has decreased most among women aged 20 to 24 – down 79% from 181.6 live births per 1,000 women of this age group in 1964 to 38.6 in 2023.

Some experts have suggested influencing factors could include economic uncertainty with the cost-of-living crisis, and difficulties finding a partner – as well as more people deciding not to have children.

The average age of mothers remained stable at 30.9, while fathers’ average age increased slightly from 33.7 in 2022 to 33.8 last year.

The biggest drops in the overall total fertility rate were in Wales (1.46 to 1.39) and the north west of England (1.53 to 1.46).

London (1.39 to 1.35), the North East (1.47 to 1.43) and the West Midlands (1.62 to 1.58) saw the smallest decreases.

The fertility rate is defined as the average number of live children a group of women would have if they experienced the age-specific fertility rates throughout their childbearing life.

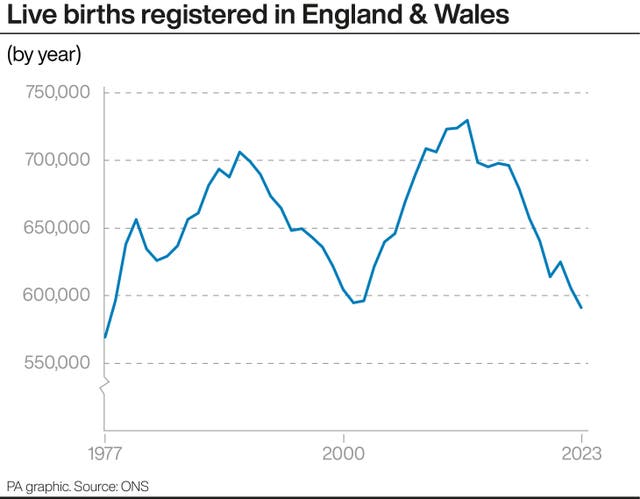

In 2023, the number of live births (591,072) in England and Wales fell to the lowest since 1977 when there were 569,259.

The data, which also covers stillbirth rates, said those fell in Wales from a rate of 4.4 per 1,000 births in 2022 to 4.0, and stayed the same in England at 3.9 stillbirths per 1,000 births.

Stillbirth rates decreased in the black, mixed or multiple, and white ethnic groups for England and Wales compared with 2022, but rates rose in the Asian and “any other” ethnic groups, the ONS said.

Stillbirth rates overall remain higher for Asian, black, and “any other” ethnic groups than the England and Wales overall rate, the statistics body added.

The Sands charity said the data shows “progress is not being made to reduce the stillbirth rate in England” and “unacceptable inequalities in baby loss also persist”, with the stillbirth rate in England and Wales among black babies still almost twice that of white babies, at 6.3 stillbirths per 1,000 total births compared with 3.4.

Greg Ceely, head of population health monitoring at the ONS, said: “The annual number of births in England and Wales continues its recent decline, with 2023 recording the lowest number of live births seen since 1977.

“Total fertility rates declined in 2023, a trend we have seen since 2010. Looking in more detail at fertility rates among women of different ages, the decline in fertility rates has been the most dramatic in the 20-24 and 25-29 age groups.”

Luton in Bedfordshire had the highest fertility rate in 2023 among local authorities in England (2.01), followed by Barking & Dagenham in London (2.00), Slough in Berkshire (1.93) and Pendle in Lancashire (1.90).

The City of London had the lowest rate (0.55), followed by Cambridge (0.91), Brighton & Hove in East Sussex (0.98) and Westminster in London (1.00).

A total of 12 of the 25 local authorities with the lowest rates in 2023 were in London.

In Wales, Newport had the highest fertility rate last year (1.63) and Cardiff had the lowest (1.16).

Prof Bassel H Al Wattar, associate professor of reproductive medicine at Anglia Ruskin University, described the downward trend in fertility and birth rates as “worrying yet persistent”, which he said might be explained by the cost-of-living crisis, as well as a reduction in available NHS funding for fertility treatments such as IVF.

In July, a report by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) found fertility treatment numbers in 2022 increased on pre-pandemic levels but that the proportion of IVF cycles funded by the NHS in the UK fell fallen to the lowest level since 2008.

Professor Melinda Mills, professor of demography and population health at the University of Oxford, said: “People are actively postponing or forgoing children due to issues related to difficulties in finding a partner, housing, economic uncertainty, remaining longer in education and particularly women entering and staying in the labour force.

“Some individuals also actively make the choice to remain childfree.

“However, there is evidence that postponing having children to later ages when the partners are less able to conceive results in increases in involuntarily childlessness as well.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here